Encouragement or Punishment? Why That's Not the Whole Story

Motivation

When managing a team, there are two common approaches to alter individual behavior: encouragement and punishment. For example, if an employee is not performing well, the manager may either encourage or reward them when they show improvement, or punish them when they fail to meet expectations. Conversely, if an employee is performing well, the manager may either encourage or reward them to reinforce their good behavior, or remove negative stimuli—something the employee dislikes, such as mundane work. However, after understanding more about behavioral science, I've come to realize that this framing of the question is not entirely accurate.

The phenomenon we are examining is the learning process through which associations are formed between environmental stimuli and behaviors. At its core, it explores how experience shapes our actions and reactions. Some behaviors are involuntary and automatic—for example, dogs naturally salivate when they see food, or humans experience pleasure when viewing beautiful or attractive people. Associations can be formed by presenting a neutral stimulus and pairing it with a desired response. Consider how a popular soft drink brand consistently features happy, attractive people enjoying parties and social gatherings in their commercials. Over time, consumers begin to associate the beverage with the positive emotions and experiences depicted in these advertisements. However, our focus lies with voluntary behaviors, which are controlled by their consequences. There are two critical dimensions to consider: the goal of the consequence and the nature of the consequence—concepts best illustrated through Skinner's operant conditioning experiments.

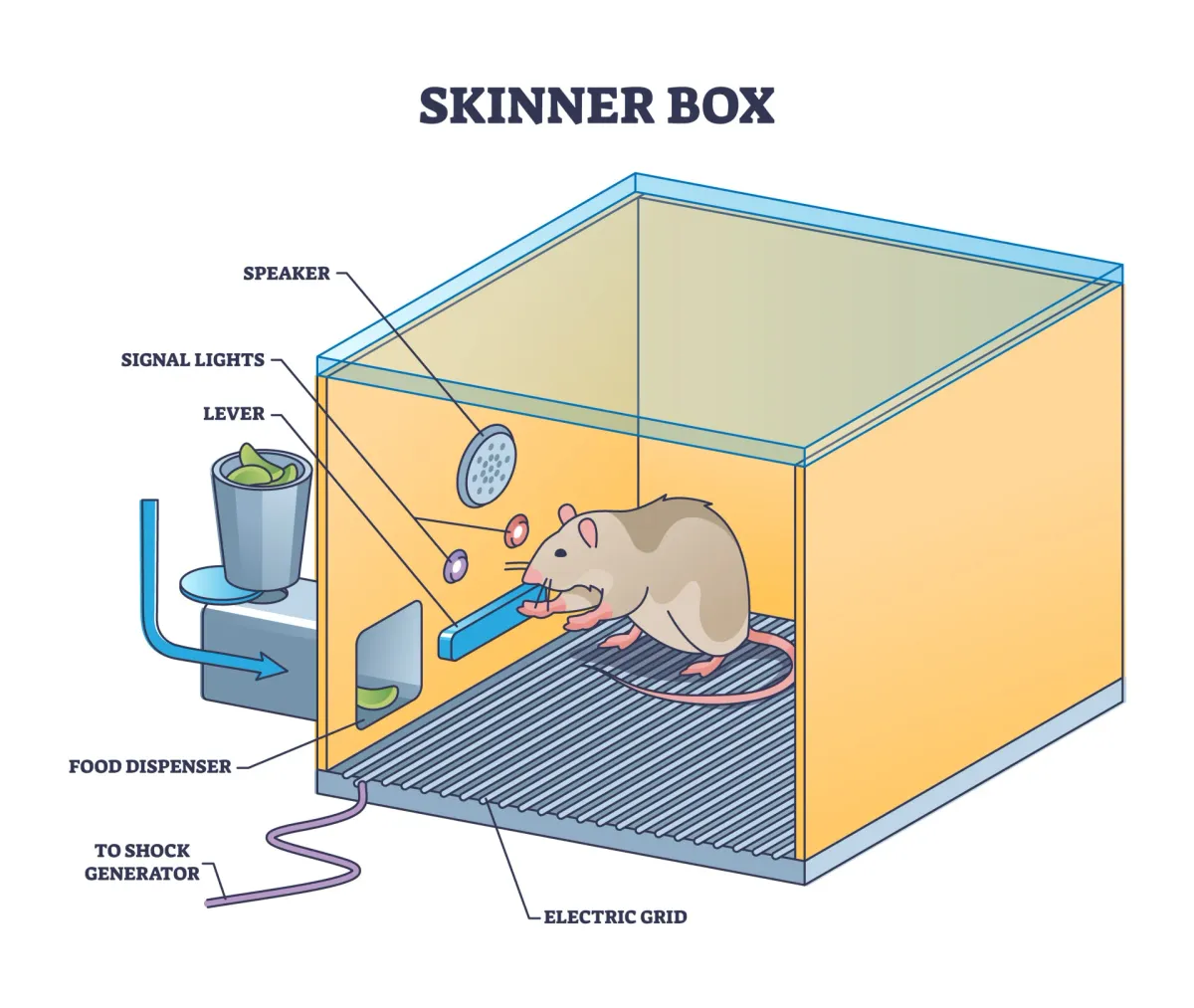

The Skinner Box

The Skinner box is a controlled environment designed to isolate a subject—typically a rat or pigeon—from external distractions. A typical Skinner box is equipped with several key components:

- Manipulandum: An object that the animal can interact with, such as a lever or button.

- Reinforcer: This mechanism dispenses a reward when the animal performs the desired behavior. The most common reinforcers are food pellets or drops of water.

- Stimulus presenters: These can include lights, sounds, or other signals that researchers can use to cue the animal about the availability of reinforcement or to signal different experimental conditions.

- Recording device: This automatically records the animal's behavior, such as the number of times it presses the lever or the amount of time it spends in the box.

- Electrified grid: An electrified floor grid can be used to deliver a mild aversive stimulus to study its effects on behavior.

There are four key terms to understand:

- The goal of the consequence:

- Reinforcement: aims to increase the frequency of a behavior.

- Punishment: aims to decrease the frequency of a behavior.

- The nature of the consequence:

- Positive: means adding a stimulus

- Negative: means removing a stimulus

Coming from outside the behavioral science field, I initially confused the concepts of punishment, negative stimulus, and positive stimulus. I mistakenly believed that punishment and negative stimulus were equivalent—that punishing someone inherently meant applying a negative stimulus. However, I learned that punishment refers to the goal of the consequence (decreasing behavior frequency), not the nature of the consequence itself. For instance, "punishing" someone by scolding them is actually a positive stimulus because we are adding a stimulus (the scolding) to their environment. The term "positive" simply means adding a stimulus—it can be pleasant or unpleasant. The same principle applies to negative stimuli, which involve removing something from the environment. Another confusion I had was believing that negative reinforcement is a form of punishment. However, negative reinforcement is actually a form of reinforcement that aims to increase the frequency of a behavior by removing a stimulus. The goal is fundamentally different from punishment.

- Positive reinforcement: Adding something good to increase a behavior

- Goal: To make the rat press a lever more often

- Setup: The box is equipped with a lever and a food pellet dispenser. The rat is typically slightly hungry to ensure it is motivated by the food reward.

- Procedure:

- The rat is placed in the box and will naturlly explore its surroundings.

- Eventually, the rat will accidentally press the lever

- Immediately upon pressing the lever, the food pellet is dispensed.

- Outcome: The rat quickly learns to associate the action of pressing the lever with the food reward. Because a pleasant consequence was added, the frequency of the lever-pressing behavior increases.

- Negative reinforcement: Removing something bad to increase a behavior

- Goal: To make the rat press a lever more often

- Setup: The box is equipped with a lever and an electrified floor grid that can deliver a mild continuous, and uncomfortable electric shock.

- Procedure:

- A mild electric current is activated on the floor of the box.

- The rat shows signs of discomfort and moves aorund, trying to escape the sensation.

- Where the rat eventually hits the lever, the electric current is immediately turned off. The unpleasent stimulus is removed.

- Outcome: The rat learns that pressing the lever is the way to escape the discomfort of the electric shock. To avoid the unplesant feeling, the rat will presse the lever more often.

This can be further divided into:

- Escape Learning: The shock is already active, and the lever press stops it.

- Avoidance Learning: A light or sound might signal that the shock is about to start, and the rat learns to press the lever during the signal to prevent the shock from ever occuring.

- Positive punishment: Adding something bad to decrease a behavior

- Goal: To make the rat press a lever less often

- Setup: The box is equipped with a lever and an electrified floor grid. Let's assume the rat has already been trained to press the lever (perhaps for food, which is now no longer provided).

- Procedure:

- The rat performs the target behavior: it presses the lever.

- Immediately upon pressing the lever, the rat receives a mild electric shock.

- Outcome: The rat associates pressing the lever with receiving a painful shock. Because an unpleasant consequence was added following the behavior, the rat will quickly learn to avoid the lever, and the frequency of lever-pressing will decrease.

- Negative punishment: Removing something good to decrease a behavior (AKA: punishment by removal)

- Goal: To make the rat stop a specific behavior, for example, standing in a particular corner of the box.

- Setup: The box is set up so that a desirable stimulus, like a steady drip of tasty water or regularly dispensed food, is available.

- Procedure:

- The rat is enjoying the continous access to the food or water.

- THe rat performs the unwanted behavior: it goes to and stands in the designated corner.

- The moment it does this, the food or water dispenser is turned off for a period of time. The desirable stimulus is removed.

- Outcome: The rat learns that performing the specific action leads to the loss of its pleasant reward. To avoud losing its reward, the fequency of the rat standing in that corner will decrease.

The four scenarios above can be summarized in the following table and the name of the theory is operant conditioning by B.F. Skinner.

| Reinforcement (Increasing behavior frequency) | Punishment (Decreasing behavior frequency) | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive (Adding a stimulus) | adding something pleasant to increase behavior frequency | adding something unpleasant to decrease behavior frequency |

| Negative (Removing a stimulus) | removing something unpleasant to increase behavior frequency | removing something pleasant to decrease behavior frequency |

Remarks: We assume that people seek for plesant and avoid unpleasant stimuli.

Reflections

Returning to the original question: to alter individual behavior, should we use encouragement or punishment? In everyday language, encouragement typically involves adding a pleasant stimulus, while punishment usually involves adding an unpleasant stimulus. However, these approaches serve different purposes—one aims to increase behavior frequency, the other to decrease it. They are not directly comparable methods, as the fundamental question is whether you want to increase or decrease the frequency of a specific behavior.

It is worth considering whether reinforcement and punishment, or adding and removing stimuli, are merely two sides of the same coin. Conceptually, increasing the frequency of one behavior is equivalent to decreasing the frequency of all other behaviors. Similarly, adding something pleasant could be viewed as equivalent to removing something unpleasant. However, I believe these distinctions remain meaningful in most practical situations.

The equivalence only holds under specific conditions: when the action space is severely limited, such that increasing one behavior directly corresponds to decreasing another, or when complementary actions are prohibitively costly or infeasible. Additionally, while mathematically an agent seeking to maximize utility might respond identically to adding or subtracting stimuli, in practice, individuals experience meaningful psychological differences between gaining something and having something taken away.

The first step is to understand the goal of the consequence. Do you want to increase or decrease the frequency of a specific behavior? The second step is to understand the nature of the consequence. Does the subject start with a neutral state, or does it already have a stimulus? Is the stimulus pleasant or unpleasant? After that, you can determine the possible options to achieve the goal.

However, there are still nuances to consider. Will punishment (decreasing behavior frequency) lead to side effects? For example, does punishing an employee for a mistake teach them not to make the mistake, or does it teach them to hide the mistake? What should be the schedule of stimulus? Should it be continuous, where reward is given every time, or intermittent, where reward is given after a certain period of time? For example, an annual predictable bonus follows a fixed-interval schedule. Does it effectively motivate behavior year-round? How would a surprise "spot bonus" for great work differ in its motivational effect? The problem of what's actually being conditioned can be unintended. For example, if you reward an employee who stays late to finish a project, are you reinforcing "diligence" or are you reinforcing "poor time management" and encouraging burnout?

Setting incentives is a very complex problem. In the end, be careful what you wish for.